Unique, "EB on Breast"

Unique, "EB on Breast"1787 Brasher Doubloon from

The Gold Rush Collection

"BARNACLES OF GOLD"

THE STORY OF DAHLONEGA'S FAMED FINDLEY MINE

Attempts to Recover the Lost Chute

Subsequently, the Findley property was sold to the Stephenson Gold Mining Company in 1863. Dr. M. F. Stephenson (assayer at the Dahlonega Branch Mint 1850-1853) sunk a 100-foot shaft at the top of the hill north of the chute. He then cut a tunnel from the bottom of the new shaft that was designed to strike the chute from that angle. His operations were halted by the scarcity of labor and the high price of powder for blasting the rock. Later operations proved that his tunnel stopped only five or six feet from the chute.

The Dahlonega Mining Company purchased the Findley property in 1866 but did little work on the mine aside from running a long tunnel designed, like Singleton’s, to strike the chute at the bottom of the incline (a distance of about 500 feet). After driving 300 feet, Superintendent Amory Dexter halted work after workers hit a belt of very hard rock. His decision was also influenced by a title dispute.

In 1868, the Dahlonega Mining Company leased the Findley and Lockhart mines to local miners Crisson and Huff. In 1871, W. R. Crisson (Huff having retired by this time) moved the Lockhart’s 24-stamp mill to the Findley and began mining operations on that property after replacing the badly worn stamps with new ones.

In 1875, N. H. Hand (General Manager for the Dahlonega Mining Company) began to develop the property in order to place it on the market. Frank W. Hall was put in charge of the work. He drove a tunnel from the Dexter tunnel to the bottom of the Stephenson shaft and successfully continued the Stephenson tunnel to the elusive chute. Hall reported taking out “about $3,000 in handsome free gold specimens and that a great deal more was left in place, the object of the work being to develop the mine for sale.”

It was during this time that “the Little Findley Mill” was erected on the northwest side of the ridge to mill the ore brought by flume from the large cut on top of the ridge started by W. R. Crisson. This mill was the 10-stamp Hall mill moved from the Lawrence Mine (located on the Mustering Ground near the Dahlonega Public Square) and was run by steam.

Findley Ridge, Backbone of the Georgia Gold Belt

In 1878, the Findley Gold Mining Company of New York City purchased the property for $30,000. According to a prospectus published by the company that year, the Findley lot “is conceded by every one to contain the largest mass of gold-bearing ores in the Southern belt.” Findley Ridge, called the “backbone” of the Georgia gold belt by mining engineers and geologists, was dramatically described as “a precipitous ridge, jutting into the valley, with almost sheer ascent of 500 feet above the level of the river.”

The celebrated Findley Vein was described in the prospectus as “a clear, lively quartz lode about three feet thick, carrying a remarkably rich ‘pay streak’ of two to eight inches, and yielding in many places almost pure masses of gold.” It went on to note that “nuggets weighing from twenty to fifty pennyweights, are sometimes broken from the quartz while taking down the vein”and “one mass of quartz and gold taken from this lode, weighing about twelve pounds, produced nearly eight pounds of gold.”

The

Findley Gold Mining Company enlarged the “Little Findley Mill”

to 20 stamps and increased its steam power. It also replaced the

24-stamp mill beside Yahoola Creek with 40 stamps and installed

steam pumps to raise water from the Findley Ditch 175 feet to the

top of the ridge for use in working the upper cut.

The

Findley Gold Mining Company enlarged the “Little Findley Mill”

to 20 stamps and increased its steam power. It also replaced the

24-stamp mill beside Yahoola Creek with 40 stamps and installed

steam pumps to raise water from the Findley Ditch 175 feet to the

top of the ridge for use in working the upper cut.

This information is confirmed by an item in the September 8, 1876, issue of Dahlonega’s newspaper, The Mountain Signal: “A ram of the largest size is throwing water into a reservoir on the summit of the hill 153 feet above the ditch....”

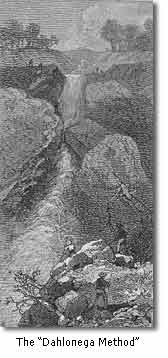

The Dahlonega Method

A

reservoir was dug at the top of the ridge to store the water, which

was released at the end of the day to wash the ore from the cuts

down to the mill. This method was apparently developed locally and

came to be known as “the Dahlonega Method.”

A

reservoir was dug at the top of the ridge to store the water, which

was released at the end of the day to wash the ore from the cuts

down to the mill. This method was apparently developed locally and

came to be known as “the Dahlonega Method.”

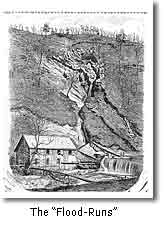

That process was colorfully described by a writer sent to Dahlonega in 1879 by Harper’s New Monthly Magazine to research and write an article on “Gold Mining in Georgia.” The article which appeared in the September 1879 issue provides wonderful eyewitness descriptions of scenes long vanished in time, such as “the ruins of the old United States Mint, looking very romantic in the sunset glow.” Many of them are illustrated with fine pen-and-ink drawings, including a dramatic scene showing great torrents of water sweeping ore down the hillside to be processed in the mill below.

“This operation is called ‘flooding’ the mine, and one evening we rode out to the Findley Mine to see it,” wrote the unnamed author. “There the cut runs straight up and down the side of a hill 500 feet high, and is in the form of a deep, irregular, vertical trench.....We climbed to the summit of a high knoll jutting up by the line of the cut, and waited. In a moment an ominous ‘grumble and rumble and roar’ was heard, which, beginning faint and far aloft, gradually grew more threatening, until there was a sudden volley of sound, and at the end of the narrow trench a mighty mass of red-brown waters came leaping over the ledge....But it was not all water, nor even mud. Tons upon tons of broken rocks were coming down through this terrible flume, rolling over and over, rattling among their fellows, grinding along the walls, bounding out of the narrow crevice, leaping high above the red spray, and falling in ringing rain upon the stony floor. The noise was a hoarse, crushing, terrific roar. The force was prodigious.”

The dimensions of the reservoir on Findley Ridge were given by State Geologist W. S. Yeates in his

Preliminary Report on a part of the Gold Deposits of Georgia

published in

1896. It was “150 feet long, 15 feet wide, and 6 feet deep,

from which water is delivered, by ditches and iron pipes, to various

parts of the open cuts, for making the flood-runs of saprolite from

the cuts to the mill, and for operating the hydraulic giants.”

The dimensions of the reservoir on Findley Ridge were given by State Geologist W. S. Yeates in his

Preliminary Report on a part of the Gold Deposits of Georgia

published in

1896. It was “150 feet long, 15 feet wide, and 6 feet deep,

from which water is delivered, by ditches and iron pipes, to various

parts of the open cuts, for making the flood-runs of saprolite from

the cuts to the mill, and for operating the hydraulic giants.”

Despite the glowing description of the Findley property and its potential described in its prospectus, the Findley Gold Mining Company apparently did not prosper. According to Yeates, this company made the error of sending a young relative of a stockholder, fresh out of mining school, to be superintendent of the mine. He was unwilling to take suggestions from experienced local miners and was unable to find the famed chute, which had been lost. After some work in the open cuts, the operation came to a halt after a couple of years.