Unique, "EB on Breast"

Unique, "EB on Breast"1787 Brasher Doubloon from

The Gold Rush Collection

An Illustrated History of the Georgia Gold Rush and the United States Branch Mint at Dahlonega, Georgia

By Carl N. LesterPreface

Due to the discovery of gold in the southern Appalachians in the early part of the nineteenth century, and the ensuing political influence of congressmen from the region, a United States Branch Mint at Dahlonega, Georgia was established by a Congressional Act in 1835.

The branch mint soon opened for business, producing gold coins only from 1838-1861. Half eagles ($5 gold), quarter eagles ($2.50 gold), and gold dollars were minted for the first time in 1838, 1839, and 1849, respectively. The only issuance of the rare three dollar gold piece occurred in July 1854. The mint struggled mightily in difficult circumstances, which included the mint's remote location, the declining deposits of gold, and the ever-changing political climate. The beginning of the Civil War saw the end of the Dahlonega Mint's brief history as a United States coining facility. Today, collectors cherish the most tangible legacy of the institution, those elusive gold pieces with the precious "D" mint mark. All Dahlonega coins are considered scarce, with some being very rare. They have their own peculiar characteristics of the minting process which many collectors find appealing. Modern collectors owe a debt of gratitude to those long-ago public servants of the Dahlonega Mint, who created some of the most interesting, avidly-collected coinage in the history of American numismatics. This is their story.

The Georgia Gold Rush

It is generally accepted that the first recorded discovery of gold by the white man occurred in 1799, in Cabarrus County, North Carolina. Conrad Reed, a boy at the time, found a 17-pound nugget in a creek on his father's farm. Incredibly, the family used the huge nugget as a doorstop until 1802, when it was sold to a jeweler for $3.50. Eventually word got out about the true worth of the gold doorstop, initiating the nation's first gold rush.

It is generally accepted that the first recorded discovery of gold by the white man occurred in 1799, in Cabarrus County, North Carolina. Conrad Reed, a boy at the time, found a 17-pound nugget in a creek on his father's farm. Incredibly, the family used the huge nugget as a doorstop until 1802, when it was sold to a jeweler for $3.50. Eventually word got out about the true worth of the gold doorstop, initiating the nation's first gold rush.

The Georgia portion of the Appalachian gold belt went unappreciated until Benjamin Parks discovered gold in 1828, in the area near which the town of Dahlonega would be settled.

Actually the first gold rush town in Georgia was called Nuckollsville, later becoming Auraria (from the Latin, meaning "gold"), which was located about six miles from present day Dahlonega. The gold discovery caused a near stampede of those seeking a quick fortune. The region near Auraria lay claim to one of the richest parts of the gold belt and many miners sought their fortune there. The area was named Lumpkin County in 1832 and Dahlonega was selected as the county seat in 1833, denying Auraria her claim to the title, and initiating the decline of the state's first gold rush town. This area had been home to the Cherokee for many generations. They were later forced by the government to leave their land for reservations in Oklahoma, a journey that became known as the "Trail of Tears."

The gold rush was exacerbated by a state-sponsored lottery, which awarded forty acres of gold-bearing land, previously owned by the Cherokee, to those holding the winning draws.

Parks may have best described the chaotic scene, "The news got abroad, and such excitement you never saw.

It seemed within a few days as if the whole world must have heard of it, for men came from every state I had ever heard of. They came afoot, on horseback and in wagons, acting more like crazy men than anything else. All the way from where Dahlonega now stands to Nuckollsville there were men panning out of the branches and making holes in the hillsides ."

It seemed within a few days as if the whole world must have heard of it, for men came from every state I had ever heard of. They came afoot, on horseback and in wagons, acting more like crazy men than anything else. All the way from where Dahlonega now stands to Nuckollsville there were men panning out of the branches and making holes in the hillsides ."

Dahlonega was aptly named, being derived from the Cherokee language, meaning "yellow money." In her earlier days known as "Licklog," Dahlonega soon became a boomtown, supporting a surrounding population of about 15,000 miners at the height of the gold rush. Symptomatic of its rapid ascension, shortages of common necessities were widespread. As might be expected in such a "rough and ready" gold mining town, there were stores, hotels, brothels, saloons, and gambling houses.

One contemporary account related, "I can hardly conceive of a more unmoral community than exists around these mines; drunkenness, gambling, fighting, lewdness, and every other vice exist here to an awful extent." "Sprawls Hotel," a tanyard in town, was an "establishment" where drunken miners were allowed to "ooze" until they were sober enough to "check out." On the other hand, one traveler thought that the Dahlonega hotels offered "comforts for the inner man...not excelled by any in the State."

Gold production increased in the decade following the gold discovery. The problem that the gold miners faced was that there was not an easy way to convert their finds (gold dust and nuggets) to a spendable medium. Raw gold could be used for payment in the local establishments near Dahlonega, but usually at a steep discount. Part of the difficulty was that the fineness of the raw gold was not easily determined. A few private coiners, including Templeton Reid, attempted to alleviate this problem, with only minimal success. Reid was a German "metal worker, cotton gin manufacturer, jeweler, watchmaker, and gunsmith" who briefly issued $2, $5, and $10 gold pieces dated 1830, initially from Milledgeville, then from Gainesville, Georgia. It was an arduous and risky task to attempt to have the raw gold coined at the Federal mint in Philadelphia, as the distance from the southern gold fields was long and uncertain. Nonetheless, the mint at Philadelphia did receive over $1.7 million in Georgia deposits from 1830-1837.

The Branch Mint Legislation

The Act of March 3, 1835 was passed by the United States Congress, which provided that "branch mints of the United States shall be established as follows: One branch at the city of New Orleans for the coinage of gold and silver; one branch at the town of Charlotte, in Mecklinburg county in the state of North Carolina, for the coinage of gold only; and one branch at or near Dahlonega, in Lumpkin county, in the state of Georgia, also for the coinage of gold only." The legislation was due primarily to the political influence of southern congressmen from the gold region.An initial appropriation of $50,000 for the Dahlonega Mint was provided by the Congress. The commissioner of construction was to be Ignatius Few,a lawyer and Methodist minister, best known as the founder of the institution known today as Emory University.

Joseph Singleton, a plantation owner from Athens, Georgia, was appointed as the new branch mint's first superintendent. He was described by the editor of theDahlonega Watchman as "altogether too weak in the upper story for any kind of business that requires an effort of mind."

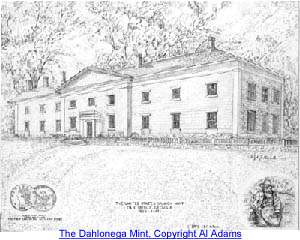

The Mint Construction

The mint building was to be constructed to the same plans as the Charlotte Mint. The architect was William Strickland, who was well known in his day as a proponent of the Greek Revival style. The basic outline of the building was that of a block letter "T," with the top of the "T" comprising the front wing. The front was to be 125 feet by 33.5 feet, while the stem of the "T" measured 53 feet in length and 36 feet in width, although evidence indicates that the front was actually constructed to a length of 127.5 feet. A building site was selected on a hill close to the town square. The 27-room structure was to have first and second stories composed of brick, covered with stucco and grooved to simulate the large granite block of the basement foundation.

The basic outline of the building was that of a block letter "T," with the top of the "T" comprising the front wing. The front was to be 125 feet by 33.5 feet, while the stem of the "T" measured 53 feet in length and 36 feet in width, although evidence indicates that the front was actually constructed to a length of 127.5 feet. A building site was selected on a hill close to the town square. The 27-room structure was to have first and second stories composed of brick, covered with stucco and grooved to simulate the large granite block of the basement foundation.

The remote location caused a gamut of associated construction problems. One would not expect to find skilled workmen and quality building materials in such a backwoods community, but the failure of the mother mint at Philadelphia to foresee and compensate for these problems only aggravated the situation. For example, the problems encountered with the making of brick could have been easily avoided by specifying granite or limestone, which were regional specialties.

Other construction problems were compounded by the fact that Commissioner Few was not a model taskmaster, making only an occasional inspection of the activities. One of Few's detractors described his efforts as commissioner, "He is labouring (sic) under permanent ill health from rupture of the lungs...all energy appears to have left him & his business habits (if ever he had any) has (sic) certainly escaped. He appears very laudibly (sic) & we may say entirely devoted to the affairs of another and better world & should be left quietly to their contemplation."

Juxtaposed with the rusticity of the community in which it was to operate, the mint was to be supplied with the latest in automated coining equipment. The most revolutionary were two steam presses, invented by Franklin Peale, a mainstay at the Philadelphia Mint, based on his recent observations in Europe, and first incorporated in the primary mint in 1836. The presses were probably the "small" version, rendering them incapable of producing coins larger than a half eagle. The presses, and other associated equipment, were shipped in 15 boxes to Savannah, sent upriver to Augusta, then hauled overland by wagon to Dahlonega.

Due to reports of the construction difficulties reaching Philadelphia, the primary mint dispatched its crack troubleshooter, Franklin Peale, who arrived in Dahlonega in November 1837, along with his daughter, after inspecting the Charlotte facility. Close scrutiny of the Dahlonega Mint edifice revealed many problems, the blame for which Peale assigned to "ignorance on the part of the contractor and the drunken and bad habits of the workmen." The longer Peale remained in Dahlonega, the worse his assessment of the building's condition became. The somewhat rambling description which follows accurately conveys Peale's exasperation at the situation: "The workmanship of the Mint edifice is abominable, a letter might be three times filled with the details of errors and intentional mal (sic) constructions, the first and greatest of which may fairly be traced to Philadelphia, in ordering a brick building in a country where there is no clay, the material employed for the brick making being the red soil of the Gold region, a decomposed granite . . . put into Brick by men who certainly deserve diplomas for Botching. " The other major problems noted by Peale included a plaster cornice (instead of the specified brick), a leaky zinc roof, and defective first floor arches (which were subsequently abandoned). Although the building was not finished and personnel were "dodging from room to room" in rainy weather, Superintendent Singleton decided that the mint was ready to begin coinage operations in February 1838.

The First "Shiners"

On February 12, 1838, the mint officially opened for the receipt and assay of gold bullion. Almost a thousand ounces of gold were deposited the first two weeks that the mint was open. An attempt to produce coinage was made on February 28, but was abandoned due to insufficient steam power.

The first coins, eighty half eagles, were struck on April 21, 1838, including one which was later sent to Philadelphia for the annual assay.

On February 12, 1838, the mint officially opened for the receipt and assay of gold bullion. Almost a thousand ounces of gold were deposited the first two weeks that the mint was open. An attempt to produce coinage was made on February 28, but was abandoned due to insufficient steam power.

The first coins, eighty half eagles, were struck on April 21, 1838, including one which was later sent to Philadelphia for the annual assay.

Superintendent Singleton wrote, "I believe our coin equal to any made in the world, both for its beauty and accuracy in its legal parts." He

went on to say the mint's coins met "a most cordial reception wherever carried." Because of a high silver content, these first coins had a slightly different color (often described as green gold), when compared to the ones minted at Philadelphia, but were nonetheless of good quality. The first Dahlonega coins to be assayed in February 1839 met the legal requirements. That month also saw the coinage of the first quarter eagle denomination at the Dahlonega Mint.

Superintendent Singleton wrote, "I believe our coin equal to any made in the world, both for its beauty and accuracy in its legal parts." He

went on to say the mint's coins met "a most cordial reception wherever carried." Because of a high silver content, these first coins had a slightly different color (often described as green gold), when compared to the ones minted at Philadelphia, but were nonetheless of good quality. The first Dahlonega coins to be assayed in February 1839 met the legal requirements. That month also saw the coinage of the first quarter eagle denomination at the Dahlonega Mint.

Superintendent Singleton seemed to be hardly up to the task to which he had been appointed. He did not keep accurate records and was taken to task by Robert Patterson, the Director of the Philadelphia Mint, "I had hoped that during your stay here in Philadelphia you had made yourself master of the system of keeping Mint accounts. As this seems, however, not to be the case, I will make out a set of specific instructions on the subject, and send them to you as soon as possible." At one point, Singleton asked Patterson to allow the Dahlonega Mint to use a screw-driven press. The Mint Director responded, "I pray you not to think of using the screw press. This is not the age nor the country for going backwards."

The Minting Process

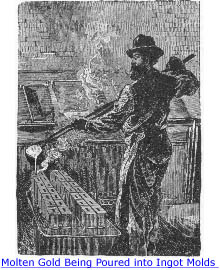

Miners were apt to deposit gold in the natural state (i.e., dust and/or nuggets), while bankers and merchants were likely to have other forms as well, including gold bars and foreign gold coins. After a receipt was issued for the deposit, mint personnel melted the gold into a homogenous mass, from which an assay slip was used to determine the fineness. Then the value of the deposit, and the corresponding equivalent in coin, was determined. The deposit was then alloyed to standard (.900) fineness by adding copper, and if necessary, silver, both of which typically carried a charge. As gold from the local fields was above the standard fineness, parting (i.e., separating out the silver) was not usually required. It was typical at Dahlonega to leave in the naturally occurring silver, and make up the balance with copper. As standard mint practice, the silver content was kept between 25 and 50 parts per thousand.

Miners were apt to deposit gold in the natural state (i.e., dust and/or nuggets), while bankers and merchants were likely to have other forms as well, including gold bars and foreign gold coins. After a receipt was issued for the deposit, mint personnel melted the gold into a homogenous mass, from which an assay slip was used to determine the fineness. Then the value of the deposit, and the corresponding equivalent in coin, was determined. The deposit was then alloyed to standard (.900) fineness by adding copper, and if necessary, silver, both of which typically carried a charge. As gold from the local fields was above the standard fineness, parting (i.e., separating out the silver) was not usually required. It was typical at Dahlonega to leave in the naturally occurring silver, and make up the balance with copper. As standard mint practice, the silver content was kept between 25 and 50 parts per thousand.

The gold melt was then cast into ingots, annealed, and passed through a rolling mill, which reduced the thickness. The resulting strip was passed through a die in the drawing bench, which resulted in a strip of gold of the proper thickness, from which planchets were cut.

After the planchets were cleaned and annealed, a steam press, located in the first floor Press Room in the rear portion of the building, struck the coins at the rate of 50-60 per minute.

The presses were so heavy that large posts had to be propped under the floor joists in the basement to keep the floor from sagging. The power to turn the press was transmitted from a belt running through the floor from the basement Engine Room, and which was connected to a steam

engine.

The presses were so heavy that large posts had to be propped under the floor joists in the basement to keep the floor from sagging. The power to turn the press was transmitted from a belt running through the floor from the basement Engine Room, and which was connected to a steam

engine.

There was a well in the basement that supplied water to the boiler. Assay coins (one for every 500 produced, with at least one from every melt) were set aside to be sent to Philadelphia. The coins could then be paid to the depositors.

Many Dahlonega coins exhibit mint-caused defects such as weak strikes and various planchet irregularities. There are several potential causes for these imperfect coins. It has been suggested by some scholars that the Philadelphia Mint, which prepared the dies, including the addition of dates and mint marks, had a practice of shipping substandard dies to the branch mints, rather than destroy them or put them in use at Philadelphia. While this may have occured, a close look at the objective evidence suggests that defective dies were not the primary cause of the weakly struck coins. There are many examples of both strong and weak strikes having come from the same die. However, there is considerable evidence in the correspondence from the Dahlonega Mint concerning mill rollers which were too soft (and did not produce quality planchets) and defective supplies of copper. The latter is thought to have caused "work hardening" of the planchets, which means that the metal would not flow properly into all design areas of the die. The Dahlonega Mint did have a considerable problem with dies cracking excessively, however.

The 1840s

Disagreements among the mint personnel were commonplace during this period. Part of the difficulty may have been a natural result of the problems inherent in establishing a highly technical operation in such an out-of-the-way community. Another problem was that the mint positions were considered "political plums" which were coveted by a number of persons outside the mint. It was not unusual for charges of corruption to be levied at those in positions of authority at the mint, usually motivated by self-interest. Others unabashedly campaigned for mint positions, writing letters to those of influence, especially members of Congress and state government. At that period of history, the political equilibrium was maintained between the Democrats and the Whigs. The Democrats held the presidency for the majority of the existence of the Dahlonega Mint; the Whigs' only White House occupancy during this period occurred from 1841-1845 and 1849-1853. Because they had been appointed due to their political leanings, mint personnel became especially nervous whenever they sensed that the balance of power had the potential to shift in Washington. Another cause for concern was a sense that the gold deposits were not as substantial as had been anticipated; there were pervading rumors that the mint would be shut down. It is interesting to note that beginning in 1840, the Dahlonega Mint was legislatively authorized to coin silver. No examples of silver coinage from Dahlonega are known today. Probable causes for the lack of silver coinage include the fact that the Dahlonega Mint did not normally part the gold (and thus had little silver) and because the small size of their presses would have prevented the coinage of the larger denomination silver pieces.

It is interesting to note that beginning in 1840, the Dahlonega Mint was legislatively authorized to coin silver. No examples of silver coinage from Dahlonega are known today. Probable causes for the lack of silver coinage include the fact that the Dahlonega Mint did not normally part the gold (and thus had little silver) and because the small size of their presses would have prevented the coinage of the larger denomination silver pieces.

One of the most interesting events in the mint's history occurred on June 10, 1840, while Coiner David Mason went to dinner. A run of half eagles was being made and upon returning Mason discovered that, "through neglect or otherwise," the bottom (reverse) die slipped a quarter turn, so that the "heads of the devices stand quartering." It is not known how many of the 1,887 half eagles minted that day had the rotated reverse, but examples are known today which have the reverse rotated 120 degrees counter-clockwise.

In April 1841 Paul Rossignol replaced Superintendent Singleton, due to the inauguration of Whig President William Henry Harrison.

Coincidentally, the amount of bullion being deposited increased significantly. Rossignol, from Habersham County, and of French descent, was 53 years old when he became superintendent. He seemed somewhat out of place in the frontier community. Continuing concerns about the possibility of the mint's closure plagued Rossignol. He also incurred the wrath of depositors who were not promptly paid; some had to wait for over a month for their Dahlonega pieces. The increase in deposits, spurred on by a very rich strike at the O'Bar Mine in May 1842, caused a strain on the ability of the mint to respond to the increased demand. Although Rossignol was accused of profiting from his office, stemming from the delay in paying depositors, a close examination of the facts revealed that his worst "crime" was being a foreigner.

In June 1843, James Cooper, who ran the mint until 1849, replaced Rossignol. Cooper, the first superintendent to actually live in the mint building, was a West Point graduate and ran the facility with military bearing. Upon assuming the new position, he noted that the people were "clamorous for coin" and he did his part in satisfying the demand.

In June 1843, James Cooper, who ran the mint until 1849, replaced Rossignol. Cooper, the first superintendent to actually live in the mint building, was a West Point graduate and ran the facility with military bearing. Upon assuming the new position, he noted that the people were "clamorous for coin" and he did his part in satisfying the demand.

Although payments to depositors had been anything but regular during the preceding period, Cooper instituted a schedule whereby mint customers were paid no later than three working days after making the deposit. Cooper's tenure was also marked by harmony among the mint personnel and good relations with the people of Dahlonega. During this period, both the quantity and quality of the coins were high. In less than six and one half years, Cooper presided over the striking of nearly 44% of the Dahlonega Mint's total coinage output.

Cooper was not without his problems, however. Although there were newspaper reports in 1844 that Dahlonega quarter eagles had been counterfeited, no further mention of the problem is found in mint correspondence. Cooper also released some anomalous coins, as at least one 1844-D half eagle is known today with a reverse rotated 180 degrees.

Even the meticulous Cooper was not immune from those after his job. One of them was former Superintendent Joseph Singleton, who levied unfounded charges against Superintendent Cooper. The charges did not stick, but Cooper, a Democrat, could not survive the election of Whig Zachary Taylor to the presidency in 1848.

One of Superintendent Cooper's last contributions included the first minting of gold dollars in July 1849.

The production of these tiny coins was no small accomplishment for the Dahlonega Mint personnel.

In October 1849, Anderson Redding, formerly keeper of the state penitentiary, became the new superintendent of the Dahlonega Mint. Secretary of War George Crawford described him as "a full-brained, round-headed, stout-built, kind-hearted, and high-mettled Christian man." He had continual problems with bookkeeping, some of which were brought about because, for the first time in her history, the Dahlonega Mint had considerable amounts of silver with which to contend.

The 1850s

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 played a significant role in the history of the Dahlonega Mint. Although the miners were admonished by the future Dahlonega Mint Assayer Matthew Stephenson not to leave (in his famous "Thar's Gold in Them Thar Hills" speech), Superintendent Redding estimated that 1,800 miners left for the California gold fields.

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 played a significant role in the history of the Dahlonega Mint. Although the miners were admonished by the future Dahlonega Mint Assayer Matthew Stephenson not to leave (in his famous "Thar's Gold in Them Thar Hills" speech), Superintendent Redding estimated that 1,800 miners left for the California gold fields.

The miners brought back gold from California, which they deposited at the Dahlonega Mint, beginning in 1850. By 1851 these deposits exceeded that of Georgia gold. Deposits from California peaked in 1853, amounting to almost 80 percent of the year's receipts.

Although deposits in 1854 were down significantly from 1853, due primarily to the opening of the San Francisco Mint (that was much more convenient to the California gold fields), the Dahlonega Mint managed to coin four denominations (dollar, quarter eagle, three dollar, and half eagle), for the first (and only) time in its history. 1854 was the last year of significant deposits of California gold at the Dahlonega Mint. Today, collectors should make note of the fact that a Dahlonega coin minted from 1851 to 1854 probably contains gold from California.

It is interesting to note that the deposit of California gold caused the Dahlonega Mint personnel to modify their normal way of processing the gold. Up until 1850, most of the naturally occurring gold that had been deposited came from the local gold fields and from surrounding states. Most of this Appalachian gold had no more than 5% silver in it. Gold brought back from California had an average of approximately 15% silver. This meant that the California deposits were below the legal fineness (.900), forcing the Dahlonega Mint workmen to part the silver from the gold. On the other hand, the typical course of action with gold that was purer than the legal standard of fineness was to add enough copper to achieve .900 fineness. It would be interesting to try and determine if the use of California gold resulted in an orange gold coloration of the resulting coinage (due to the probability that most of the silver was removed). As previously mentioned, it was standard practice at Dahlonega to leave in the naturally occurring silver if possible (which could run as high as 5% in gold mined locally), which imparted a lighter, green gold hue to the coins.

A lawyer and former state treasurer named Julius Patton was appointed by the recently elected Democrat President Franklin Pierce and replaced Redding in July 1853. Patton, a States' Rights Democrat about thirty-five years old, was described as being "efficient without being noisy." Problems faced by Patton included the dilapidated condition of the mint, declining gold deposits, and problems with the coining process.

In late 1853, the Dahlonega Mint was directed by the Philadelphia Mint to reduce the silver content of the coinage to 8 parts per thousand. Elemental analysis of coins dated 1854 confirm that the silver content was reduced significantly.

The quality of the coins struck at the Dahlonega Mint suffered during the mid-to-late years of the decade. If awards were made for this dubious distinction, they would probably be given to the 1860-D gold dollar, the 1856-D quarter eagle, and the 1855-D half eagle. It is also known that the 1856 assay coins were outside the allowable weight tolerance. As the key production personnel during this era (Coiner John Field and Assayer Isaac Todd) were both experienced, the fault probably lay elsewhere. Both had previously served in the same capacities during the 1840s when the best coinage had been produced (Field from 1848-1849 and Todd from 1843-1850). Likely culprits include soft mill rollers, excessive "work hardening" from supplies of defective copper, and out-of-tolerance weighing scales.

The quality of the coins struck at the Dahlonega Mint suffered during the mid-to-late years of the decade. If awards were made for this dubious distinction, they would probably be given to the 1860-D gold dollar, the 1856-D quarter eagle, and the 1855-D half eagle. It is also known that the 1856 assay coins were outside the allowable weight tolerance. As the key production personnel during this era (Coiner John Field and Assayer Isaac Todd) were both experienced, the fault probably lay elsewhere. Both had previously served in the same capacities during the 1840s when the best coinage had been produced (Field from 1848-1849 and Todd from 1843-1850). Likely culprits include soft mill rollers, excessive "work hardening" from supplies of defective copper, and out-of-tolerance weighing scales.

Receipts at the Georgia mint continued to decline in the late 1850s, after the California gold deposits had slowed to a trickle. There was some hope of increasing deposits brought about by several events, including the Findlay Chute discovery in 1857 and the prospects for hydraulic mining by the Yahoola Company in 1859, but history was waiting to intercede.

The 1860s

George Kellogg became the sixth and final superintendent of the Dahlonega Mint in October 1860. Kellogg was a successful businessman and former member of the state legislature. Georgia Governor Joseph Brown described him as "a Christian, a moralist, a man worthy of imitation. " Georgia seceded from the Union on January 19, 1861.

George Kellogg became the sixth and final superintendent of the Dahlonega Mint in October 1860. Kellogg was a successful businessman and former member of the state legislature. Georgia Governor Joseph Brown described him as "a Christian, a moralist, a man worthy of imitation. " Georgia seceded from the Union on January 19, 1861.

The mint coined 1,597 half eagles dated 1861-D in February; the coinage was duly reported to Philadelphia. Although the working records of the Dahlonega Mint are not extant, it has been estimated by Clair Birdsall that an additional 1,600-1,700 half eagles and 2,750-3,250 gold dollars dated 1861-D were struck after the February coinage. Although the additional strikings were accomplished by the same personnel who had executed the earlier coinage of half eagles (and not "rebel forces," as is so often stated), the subsequent mintage was not reported to Philadelphia. Dahlonega coins dated 1861 are among the most coveted from this colorful, short-lived mint. It is interesting to note that a significant portion of the gold deposits for 1860 and 1861 came from the Pike's Peak region of Colorado.

In April 1861, Superintendent Kellogg submitted his resignation to U. S. President Abraham Lincoln. In the letter he stated, "Georgia has turned all public property...of the United States over to the Confederate States Government." On May 14, the Confederate Congress voted to close the mints at New Orleans and Dahlonega effective June 1. Although the Confederate government was petitioned by the townspeople of Dahlonega to keep the mint open, there is no evidence that additional coinage took place. Superintendent Kellogg completed the mint records, shipped approximately $17,000 in gold coins and $10,000 in uncoined gold and silver to Charleston, and sold some of the remaining supplies.

He completed a detailed inventory of mint property, locked the mint records in the vault, and turned the mint building over to a caretaker on June 28. During its 24 calendar years of coinage operations, the Dahlonega Mint had produced just over $6.1 million in gold coins.

The mint facility served as an assay office and repository for the Confederate Treasury during the Civil War. Consideration was given to continuation of the facility in its former capacity, or as an assay office. Accordingly, in the summer of 1865, an inspection of the mint property was made at the request of the United States Treasury Department, with estimates given for its reactivation.

The North Georgia Agricultural College

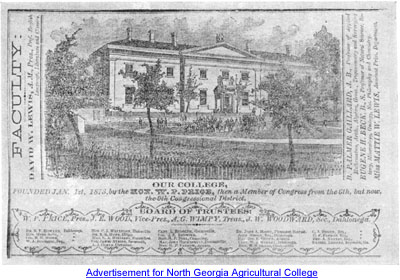

Neither of the two proposed uses came to fruition, and the building was donated in April 1871 to the State of Georgia, for use as an educational facility. The former mint building became the main facility of the newly created North Georgia Agricultural College in 1873.

Neither of the two proposed uses came to fruition, and the building was donated in April 1871 to the State of Georgia, for use as an educational facility. The former mint building became the main facility of the newly created North Georgia Agricultural College in 1873.

Classes were held in the building, which also served as the residence for the family of the college president, as well as some of the faculty and students. Fire broke out early in the morning of December 20, 1878 and the former mint structure was destroyed in the ensuing conflagration.

The townspeople of Dahlonega were determined to see that the college continued and a new college building was constructed on the old mint's undamaged granite foundation, being completed in 1880.

- Carl Lester

Click here for the Bibliography