Unique, "EB on Breast"

Unique, "EB on Breast"1787 Brasher Doubloon from

The Gold Rush Collection

Jennie Wimmer Tested Gold in Her Soap Kettle

By Anne Dismukes AmersonMuch has been written about James Marshall's discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill in 1848, thereby precipitating the California Gold Rush. Little is known, however, about the one person present who was able to recognize the shiny rock which others believed to be mica or fool's gold. To prove it was the real thing, Jennie Wimmer boiled the nugget in her soap kettle. The rest of that story is history, but who was the mysterious "Mrs. Wimmer" who is mentioned only briefly, if at all, in the many accounts of the California Gold Rush?

Elizabeth Jane "Jennie" Cloud Wimmer |

While Martin Cloud and his son James were mining, Jennie and her mother Polly contributed to the family income by operating a boarding house and eating establishment for miners. Whenever Jennie had any free time, she was out prospecting with her gold pan and soon developed a sharp eye for gold-bearing ore.

The winter of 1839-40 was unusually severe and wet, which not only impeded mining but also caused widespread illness among the miners. Jennie reported devoted herself to nursing the sick until she became seriously ill herself.

A rare early account of her life says that she was nursed back to health by a young miner named Obadiah Baiz (also spelled Bays and Bayse), whom she later married. It seems more likely that they married in Virginia before coming to Georgia. No marriage record has been found either in Virginia or Georgia, but on file in Patrick County, Virginia, is Obadiah's application for a license to marry Elizabeth Jane Cloud along with a note from Jennie's father giving his written consent for the marriage, since she was under age. Both are dated August 4, 1838.

There is no record of how much success the Cloud family had during their sojourn in Georgia, but they apparently lingered there only a couple of years. In the summer of 1840, Obadiah and Jennie decided to immigrate to Missouri and become farmers instead of miners. It was a journey that almost claimed Jennie's life. While crossing the rain-swollen Mississippi River, a log struck the plank ferry and caused it to capsize. Thrown abruptly into the churning, muddy waters, Jennie managed to save herself by grasping the tail of one of the oxen and clinging to it as the beast struggled ashore. After arriving in Missouri, Jennie and Obadiah were neighbors with Peter and Polly Harlan Wimmer. Unfortunately, both Obadiah Baiz and Polly Wimmer died of a deadly malady called "wasting fever" (probably cholera) in 1843, leaving Jennie with two small children and Peter with five. It is not surprising that the two bereaved parents married the following year.

Peter Wimmer |

After six weary months of travel, the party arrived at Sutter's Fort on November 15, 1846, just days ahead of the ill-fated Donner-Reid Party, which was caught in a snowstorm while crossing the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Rescuers sent by Captain John saved forty-seven of the party, but the other forty-two perished.

Soon after they arrived, Peter and his older sons went off to fight in the Mexican War, leaving Jennie and the younger children at Sutter's Fort, which was famous for its hospitality to travelers. Jennie had the first child to be buried in the new Sutter's Fort cemetery, but it is unclear whether this was a Baiz child or a Wimmer child. Not long after hie enlistment, Peter was severely injured when a wagon loaded with a cannon turned over on a rough road. His injuries forced him to return to Sutter's Fort, where he was employed by Capt. John Sutter.

Capt. Sutter cultivated many acres of wheat, but he needed a flour mill to grind it. In order to build a flour mill, he needed lumber, but there was a shortage of timber in the area around the fort. He went into partnership with a wheelwright named James Marshall to scout out a suitable location and build a sawmill. Marshall came back with reports of a well-timbered valley on the South Fork of the American River about fifty miles east of Sutter's Fort. The Indians living there called it "Culluma."

As foreman, Marshall hired a crew of thirteen Mormons and some local Indians. Peter Wimmer was made assistant to Marshall and put in charge of the Indians digging the mill race. His wife Jennie was employed as camp cook. Peter's sixteen-year-old son John went in the advance party with Marshall, while the rest of the Wimmer family followed in two ox-carts loaded with tools, equipment and food supplies. They arrived at Culluma (Coloma today) around the first of September, 1847.

Reconstruction of the Wimmer Cabin |

"On Christmas morning in bed she swore

That she would cook for us no more

Unless we cum at the first call

For I am Mistress of you all."

Jennie was undoubtedly vastly relieved when the Mormons built a new cabin for themselves and took over doing their own cooking, especially since she was pregnant at the time. Benjamin Franklin Wimmer was born the following spring.

When the millrace at Coloma was completed and tested, it was discovered that the foundations of the mill had been set too low. In order to deepen the water course running under the mill, Peter Wimmer's crew excavated the channel with picks and shovels during the day. At night they opened the gates of the forebay to allow the water to run through the ditch and wash away the sand and gravel.

When James Marshall made his usual inspection of the mill race on the morning of January 24, his eyes were drawn to something sparkling in the water. There are several different accounts about who was present and whether more than one nugget was found at the time. According to sworn depositions made in later years by both Jennie and Peter Wimmer, Peter was with Marshall at the time of the discovery.

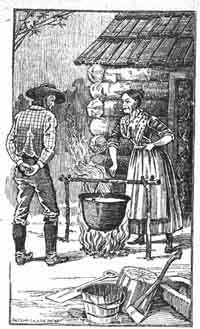

J.W. Marshall and Mrs. Wimmer Testing Gold in Boiling Soap. From California Gold Book; Its Discovery and Discoverers by W.W. Allen and R.B. Avery, published in San Francisco in 1893. |

There was apparently much skepticism in the camp about Marshall's find, many scoffing that it was only mica or fool's gold (iron pyrites). Apparently none of those present had ever seen gold in its natural state----except for Jennie Wimmer. When interviewed by the San Francisco Bulletin in 1874, she recalled having immediately recognized the small nugget brought to her young son Martin on that fateful day back in 1848. "I said, 'this is gold, and I will throw it into my lye kettle, and if it is gold, it will be gold when it comes out,'" were her reported words. On this particular day, Jennie had the chore of making soap for washing clothes. She had already made liquid lye by leaching creek water through wood ashes and adding it to a pot of accumulated left-over cooking grease. She knew that unlike mica or fool's gold, real gold would not be affected by being submerged in this pot of caustic potassium carbonate.

"I finished off my soap that day and set it out to cool and it stayed there till next morning," Jennie continued. "At the breakfast table one of the workmen raised up his head from eating and said, 'I heard something about gold being discovered. What about it?' Marshall told him to ask Jennie and I told him it was in my soap kettle....A plank was brought for me to lay my soap on. I cut it in chunks but it was not to be found. At the bottom of the pot was a double handful of potash which I lifted in my two hands and there was the gold piece as bright as could be."

Marshall took the gold to Sutter's Fort, where Capt. Sutter subjected it to a whole battery of tests including hammering it and exposing it to nitric acid from his apothecary. Every test proved positive. Capt. Sutter gave each of the mill workers a pocket knife in an attempt to pledge them to secrecy, but such a discovery was bound to be found out.

Ironically, it was one of the Wimmer children who "spilled the beans" to a teamster delivering a wagon load of supplies to the camp at Coloma. As soon as he got back to Sutter's Fort, the teamster excitedly shared the news at Charlie Smith's store, and Smith in turn told his partner, Samuel Brannan, who owned a newspaper in San Francisco. Articles about the discovery of gold began appearing in the papers, and a special edition was sent East by pony express. By spring, the coastal towns were drained of manpower as men abandoned farms, shops, and ships and flocked to the foothills carrying frying pans and spoons to use for panning.

By the end of 1848, out-of-state gold seekers were joining the locals, coming not only from Oregon to the north and Mexico to the south but even sailing in on ships arriving from Hawaii and Chile. New York newspapers picked up the story recorded in The California Star, which Brannan had sent back to the States, and men from all walks of life became infected with "gold fever." Many sold everything they owned in order to purchase supplies and transportation to "the new El Dorado." Some bought passage on ships sailing around the southernmost tip of South America, while others took a short cut by walking across the Isthmus of Panama and catching another sailing vessel once they reached the Pacific coast. Many traveled overland by wagon or even on foot pushing wheelbarrows.

To those who had come to California to make a different kind of life, it seemed as though the whole world came rushing in to interrupt their plans. Capt. Sutter was forced to shut down many of his extensive operations due to shortage of labor. Two thirds of his wheat crop went unharvested for lack of workers. Squatters settled on his land, butchered his cattle, and stole his horses. His sawmill at Coloma was forced to shut down after cutting only a few thousand feet of timber. Sutter's 150,000-acre empire was soon gone with the wind.

Reconstruction of Captain Sutter's Saw Mill |

The Wimmers left Coloma soon after gold was discovered there and lived in several different locations in both northern and southern California in the ensuing years. Peter died in San Luis Obispo County on August 17, 1892. His obituary stated: "Deceased was at one time considered wealthy, but like a good many more 49ers, was too liberal for his own good."

The exact date of Jennie's death is not known but was probably not long after she and Peter signed depositions before the Clerk of the Superior Court of San Diego in 1885. She is buried in a pioneer cemetery in San Diego County, and her grave is marked by a small stone inscribed simply, "Mrs. Wimmer." The nugget which Jennie always claimed was the first one Jim Marshall found in the millrace at Sutter's Mill and gave to her as a keepsake eventually ended up in the Bancroft Library at the University of California. A nugget which the Smithsonian formerly described as the first nugget found by Marshall at Sutter's Mill is now described as "one of the first" as a result of information sent to them by Wimmer descendant Bertram Hughes of Vacaville, California.

A closeup of the Wimmer Nugget in the palm of a hand. |

There has been little mention of Jennie Wimmer in the annals of history, and the few references to her have been brief and frequently contradictory. In recent years her descendants have been working to set the record straight and see that she receives the recognition she deserves. Their research has revealed the intriguing life story of a high-spirited and adventuresome woman whose life would have been exciting and historically significant even apart from the role she played in the start of the California Gold Rush.