Unique, "EB on Breast"

Unique, "EB on Breast"1787 Brasher Doubloon from

The Gold Rush Collection

Inns and Inn Keepers of the Gold Fields of Lumpkin County, Georgia

by Sylvia Gailey Head(January 2001)

Nature created a narrow ridge of land in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Rainfall on one side of it finds its way into the Chestatee River, while that on the other side goes into the Etowah. These streams are within two miles of each other at this point, but then go in different directions and, joining other tributaries, reach the ocean many miles apart. A squatter by the name of Dean built a house, and the ridge became known as "the William Dean Place." The little ridge was adorned with deposits of gold and was within the homeland of the Cherokees until the gold was found by Benny Parks, a white man. News of the discovery spread like wildfire; hordes of men came from every state that Benny had "ever heard of," and they came from over the seas. They came with picks and shovels to dig for gold, creating chaos among themselves and with the Cherokees. These people were intruders and were known by that name thereafter. The State of Georgia decided it was time to bring order into the territory - a rich territory, so she extended jurisdiction and, by land lottery, again gave the red man's homeland to the white man - not the intruders, for they were excluded in the draw, as was a group called "the Pony Club," who invaded the Indians' homes and destroyed their property. Those entitled to participate were men who were residents of Georgia for two years, but had not been successful in any other lottery (two draws for a married man), and old soldiers of her wars or the widows and orphans of soldiers. Many prize winners had no intention of moving into the territory, or means to mine, so there appeared another group called Speculators, who bought up the lots and sold them to still another group - those with money and the knowledge of mining. Now another group was needed - lawyers to settle disputes over lots and prepare bills of sale.

Nuckolls' Tavern

The miners were living in hastily built shacks wherever they found gold, but the other people needed a place to stay. Nathaniel Nuckolls had known an easier and surer way to get the gold. He built a tavern on the ridge and sold drinks to the miners for the grains of gold that would stay on the point of a knife, and the place became known as Nuckollsville, sometimes spelled "Knucklesville" due to the numerous fist fights in the place.Mrs. Paschal and Sons Hotel

Principle Street of Auraria in 1932. To the reader's right on the vacant lot stood the Paschal Hotel. The two story building on the left is the Graham Hotel of Civil War Times. Courtesy of History of Lumpkin County by Andrew W. Cain |

One of the hotel's patrons was the former Vice President, John C. Calhoun, now a powerful Senator from South Carolina. He had stayed at the hotel two weeks at a time while supervising his gold mining business in the vicinity. The miners liked to congregate on the hotel porch at night and listen to the eloquent man tell of events in the Nation's Capital and around the world.

Soon the little ridge had as many as one hundred buildings. Twelve or fifteen were law offices; several were taverns; there were also a few stores and a newspaper. Now, the citizens decided that they should have a better sounding name than somebody's "ville." With Calhoun's help, they chose "Auraria," from the Latin, indicating gold.

The county had been named "Lumpkin" and a county seat and government had to be established. Naturally, the Aurarians thought it would be in their town, for there was no other town. Then they learned that the lot Auraria was sitting on was fraudulently drawn by John R. Plummer, who had posed as a married man in order to get an extra draw in the lottery. When his deed became null and void, there wasn't time to make everything legal, so a lot five or six miles away, where there was a superb spring, was chosen for the county seat, and was eventually named Dahlonega. Its town lots were being sold on the fourth of July, 1833, the day Auraria was planning a big celebration, with barbecue already in the making and orators and toastmasters selected. The loyal refused to let their plans be wrecked and the barbecue went on. A lawyer, Milton Gathright, was the substitute reader of The Declaration of Independence, and everybody and everything was toasted: from George Washington down to the man making the barbecue; from the United States down to the local newspaper. Milton Gathright offered a toast to the new seat of government, "Our county site; conceived in sin, brought forth in iniquity, cradled in corruption and located upon destruction," and glasses were held high. However, people left Auraria like rats deserting a sinking ship. Milton Gathright was one of the last to go, but he finally hung up his shingle in Dahlonega. Grandma Paschal never left. At the age of 94, she was laid to rest in Auraria's cemetery beside her soldier husband, whose body she brought from Oglethorpe County shortly after she came to the narrow little ridge.

All of this came from newspapers, especially the Western Herald that came to Auraria when the town was quite young, but left when it was dying. The information can be found in Andrew W. Cain's History of Lumpkin County and E. Merton Coulter's Auraria .

The Graham Hotel

|

Miss Fanny Woods told Andrew W. Cain that she could remember the Paschal Hotel and she said that it was torn down and moved some twenty miles to Gainesvillle. The lot where it stood in Auraria is still vacant, across the street can be seen the dilapidated Graham house of the Civil War days. It was sometimes used as a hotel and Harrison Riley stayed there when he was in Auraria. The story of Riley is to follow.

The Choice House

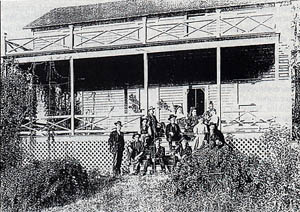

The hotel built by John Choice before 1837. The students in the foreground make the date of this picture some time after 1872. The Masonic Hall, the white two story building in the background, verifies the location of the hotel. Courtesy of Enoch J. Hicks |

During the month of October, 1833, John Choice bought eight lots in the new town of Dahlonega from the Inferior Court of the new County of Lumpkin. They compose the entire block on the south-east corner of the town square, with the exception of lots 85 & 88 which faces today's Choice street. He also obtained lots 91 & 92 in the next block. Now he owned all the lots along Park Street to the place where the first Methodist Church building was erected and the new one stands today. On his property, he built Dahlonega a hotel.

Many years ago, the seventy-six year old W. Reece Crisson, in reminiscing for the newspapers, placed the Choice House on lots 79 and 80, the corner of Park and Main Streets facing the town square. He also said that Choice was among the early merchants of Dahlonega. The logical place for his store house faced Main Street adjoining the hotel. Another old Citizen said that Dahlonega's early hotels "were large and commodious and the comforts for the inner man were not excelled by any in the state."

The only means of transportation, in that day, was by horseback or horse drawn vehicles so it took as much space for a man's horse as for himself. The stage coaches, with no less than six horses, and the hotels horses had to be considered also. Therefore, all the space in back of the hotel with lot 82 on Choice Street and 91 and 92 were designated "stables"

In the meantime, John had taken Tully and Cyrus Choice of DeKalb County as partners and he became John Choice and Company.

G. W. Featherstonhaugh F.R.S., F.G.S. wrote in his Journal, reproduced in A Canoe Voyage up the Minnay Sorter, "August 11,1837, I left Gainesville by stage at 3:30 a.m. and arrived in Dahlonega ten and a half hours later. Here I got a room at a tolerably clean house run by a person named Choice". Senator John C. Calhoun met him there and the Geologist from England wrote at length about their evening together. Featherstonhaugh obtained a horse and the two men spent the next day visiting mine sites. When they returned to the hotel at night, they found Governor Schley of Georgia there.

Paul Rossignol, the second superintendent of the Dahlonega Branch of the United States Mint, his wife. Adrienne Dugas, and daughter, Emily lived at Choices from the spring of 1841 to the summer of 1842. This was revealed in the family correspondence written mostly in French. When Paul's parents, of royal blood, had to leave France, they settled in Santo Domingo where Paul was born. When he was six years old, a slave uprising caused a move to the United States.

John D. Anthony, Jr. (Jack) did extensive searching to help with this article. Among court records and the records given to him by his mother, Madeleine, he found a deed made to a group of men under the name of Miller, Ripley and Company, Charleston, South Carolina. It was signed by John Choice and Tully Choice in payment of their promissory notes given during the years 1836, 1837, 1838, and 1840. Among other things, the Choices deeded the town lots that they bought in 1833 with their appurtenances and improvements. These included lot #79, where the hotel stood. Household furniture was included in the deed, naming such things as 36 bedsteads with straw mattresses and feather beds, 48 windsor chairs and other bedroom, dining room and kitchen furniture. Two bay horses and a four-wheeled pleasure carriage were items in the deed.

The 49 year old John Choice died September 2, 1842, leaving wife, Mary Ann, and three children. From the minutes of the Masonic Lodge, it is learned that Mary Ann then ran the hotel: At a meeting on January 24, 1845 the Masons resolved to crepe the jewels of the lodge and to wear black ribbons on their arms for sixty days as a memorial to Andrew Jackson, who had just died. On that day they marched through the town to the Methodist Church. The return march was "from the church to Mrs. Choice's hotel , around the Court House by the course of the sun, thence up Main Street to the Lodge room." Mary Ann Choice and John M. Gregory were married November 30, 1847. The date that she gave up the hotel is not known.

The next time the Choice lots, including lot #79, were mentioned was in a deed giving them to Isaac L. Todd by Horatio Miller of the state and city of New York and Charles V Chamberlaine of Charleston, South Carolina.

The Globe Hotel

In the 1850's the local newspaper was advertising "The Globe Hotel, Isaac L. Todd, Proprietor" and was announcing, "The Dahlonega Stage Lines Leaves from the Globe Hotel". Todd, born in Pennsylvania, was assistant assayer of the Dahlonega branch of the United States Mint from its inception in 1837 to 1843 when he was made assayer. Being a Democrat, he was forced to stand aside during the Whig administrations of Taylor and Fillmore. Not until December of 1850, did the Whigs succeed in ousting Todd. A. W. Redding, the newly appointed superintendent of the mint, wrote in a letter to George W. Crawford, "Mr. Todd has purchased recently, a store and a tavern in the village". From 1850 until 1853, Todd waited in Dahlonega for the Democrats to regain the presidency and he, his old job. Becoming assayer again, he advertised a stock of goods at cost. Todd remained assayer until the onset of the Civil War when the mint was closed. He then moved to Rome. Georgia and became a conductor on a railroad.The Lawrence House

Isaac L Todd made a deed on April 3, 1854 to William G. Lawrence and James A. Lawrence giving them Choice's original lots (with improvements) for the sum of $2,000. This included the lot where the hotel stood. The place now became The Lawrence House. On June 30, 1857, the Lawrence men gave Todd a morgage deed on the property known as the "Lawrence House which originally belonged to John Choice, deceased" May 30.1859. the property "known as the Lawrence House" was sold at Sheriff's sale at the suit of Isaac L. Todd against William G, Lawwrence and James A Lawrence. Harrison W. Riley was the highest bidder. Riley sold the property to William Roberts, President of the Augusta and Dahlonega Mining Company on May 4, 1862. It was still being called the Lawrence house. Since it had not changed names, the assumption is that the Lawrence men were managing the hotel under lease.All that is known about the Lawrences is: William G. Lawrence was an employee in the assay department of the Mint from 1849 to 1854 and his name was connected with some of the gold mines. He was born in South Carolina, was married to Rossana Harkins, a second marriage. There were five children in his family in the 1850 census, one of whom was named James. There are indications that this was James A., the partner in the hotel business. All that is found about James A. is that he picked up some nice nuggets in the streets of Dahlonega after big rains.

According to Jimmy Anderson's article, "The Burnside Family of Lumpkin County" published in the Winter 1989 issue of The North Georgia Journal, W. A. Burnside bought the Lawrence Hotel in 1877 and it became the Burnside Hotel.

The Burnside family came to Dahlonega in 1850 but they were in the county in the Shoal Creek District in 1848. James W. came first and established a successful mercantile business. He was soon followed by his mother, Catherine, and twin brothers, Thomas E. and William A. Thomas died in 1851. Mrs. Burnside died in 1874. She had been a widow since 1828 when her husband was killed in a duel with political adversary, George Walker Crawford, who later became Governor of Georgia. The details of this duel have been told by Jimmy Anderson and by Lucian Lamar Knight in his book, Georgia Landmarks, Memorials, and Legends.

James Burnside's store flourished and William A. bought and published a newspaper and became Judge of the Probate Court. He went into partnership with his brother under the name of J.W. and W. A. Burnside Company. He repaired the rambling two story Hotel of 15 guest rooms, the family living quarters, the Dahlonega Post Office and large porches. The hotel with the stables covered about one and one-half acres.

James Burnside died in 1884 of consumption and the Burnside fortune went to William A. who continued to be a leading citizen of the town. In a few years, a series of little strokes affected him mentally and he went to the insane asylum in Milledgeville where it was thought he would get better medical attention. He died there in 1891 at the age of 64 years.

The Burnside estate was quite large and W. A. had willed a good portion of it to Thomas E. Dyer, Mary Estalina Dyer and James W. Dyer, children of Arrena Dyer. It seemed to be generally known that James Burnside was the father of these children. William requested, but did not require, that the Dyer children change their name to Burnside when they reached the age of twenty-one, which they did. In time they had families of their own and "the Burnside family of Lumpkin" lives on.

The settling of this large estate began after 1891 and it was so involved that research has not yet revealed who got the hotel; however, without knowing the name of the new owner, it can be said that the name of the hotel was changed. Judge Ulysses V. Whipple of Cordele, Ga. visited Dahlonega in 1903. He wrote in his pictorial diary, published by his granddaughter in her book Reflections of Northeast Georgia, "There were two hotels in Dahlonega. I stopped at the Dahlonega Hotel, the oldest building, but said to be the best hotel. I found a good many students there." Judge Whipple made several pictures of buildings in the town and the one with the sign on the front "The Dahlonega Hotel" is definitely the old Burnside. The hotel captioned "The Other Hotel" is easily recognized as the one Harrison Riley built. Under a picture of the Lumpkin County Courthouse, he wrote, "I believe this is the only instance I know of where the post office is in the county courthouse." So, the post office had been moved out of the hotel.

The changes in ownership of Dahlonega's first hotel were revealed in deeds. These were found in Lumpkin County records with the assistance of Carol Seabolt, Jack Anthony and Al Adams.

The Choice/Globe/Lawrence/Burnside/Dahlonega hotel burned in 1904.

Helen Head Green, daughter of Dr. Head and "Aunt Nine," remembers that one year in the next decade, almost all of the block on the southeast corner of the town square was Tom Smith's cabbage patch, a lucrative crop for farmers due to the special taste of mountain cabbage. The plants were a welcome sight after looking at the unsightly burned over block for so long a time. However, when the crop was harvested and the discarded parts of the cabbage were left on the ground to rot, the unpleasant odor made the block a disgrace again.

Millard Shelton came to the rescue. When automobiles were beginning to be plentiful, he built a gasoline station on the corner of Park and Main and a home on the corner of Park and Choice. Today, the Chamber of Commerce and Welcome Center replace the station and his home is occupied by Vintage Music. A building housing the Park Street Restaurant and some offices is in between them in the middle of the cabbage patch.

The stable lots in the second block were bought by the Head brothers. Homer, the doctor who would be 132 years old if he were living today, bought the first lot and built a two story, eleven room (counting the garret) home that had a wrap-around porch on two sides. A part of the lumber that he used was the Baptist Church's dismantled first building. The doctor was then a bachelor and his Aunt Vashti kept house for him until he married Nina McClure, who later became Dahlonega's "Aunt Nine," and a leading citizen of the town. Brother Gordon's home was also a large structure.

Aunt Nine, who loved building houses and repairing old ones, built a little house between the Head homes during the 1930's. It was occupied by Graham Dugas, a miner who caused Lumpkin's last gold excitement when he discovered a rich pocket of the ore at the old Calhoun mine.

This was the era of the leisure living, fun loving Dahlonega, and the time when the Gold Rush Celebrations started. But at that time, they were more like a homecoming than a tourist attraction.

Today, Doc's home is occupied by Rick's Restaurant. Gordon's home is an apartment house. The little house between them, remodeled and enlarged, is The Royal Guard Inn, a Bed and Breakfast that serves real breakfasts.

The Eagle Hotel

Eagle Hotel, later to be named the Besser House, Halls Villa, and eventually the Wigwam. Courtesy, Georgia Department of Archives and History. |

Reams have been written about Harrison W. Riley, but little of it was good until he died. These people believed that "a decent and proper respect to the memory of the dead was a duty which man should never fail to perform toward his fellows." The newspaper started the account of Riley's demise with, "At last, the summons has come and called from this earth to eternity Gen. H. W. Riley, perhaps one of the most noted and strong minded men that the world has ever produced," and it added that he came to this country a "penniless orphan boy and by an industry and energy that has never had an equal, he accumulated a vast fortune."

The court records are full of Riley's trickery and gambling on his road to riches. One man sued the "General" for getting him drunk in a social way and buying his land for nothing. A hog drover claimed that Riley bought his hogs for five cents per pound, with the stipulation that he tell everybody that the price was two cents per pound. When delivery was made Riley paid only two cents, saying that everybody knew that it was the price agreed upon. Some disagreements ended in fights. One man asked for $5,000, claiming that "Harrison W. with force and arms, to wit with swords, knives, dirks, sticks, rocks, fists, hands, feet and teeth, furiously and violently assaulted and beat your petitioner." Another mentioned "a certain walking stick three feet long and one inch in diameter of hickory wood," that Riley carried with him and used freely in his arguments.

The obituary continued, "He has held many offices of distinction and has always with only one or two exceptions represented this county when he desired so to do, and died in harness."

Less than a month before this date the same paper carried an account of the last election and reported, "The jug has been victorious and H. W. Riley has been elected by a plurality of sixty-three."

Next Riley was praised for naming in his will (made a short time before he died) several of his children, including a little girl "name not recollected." Riley did not marry any of their mothers or anyone at all.

The newspaper article concluded with, "His remains were interred on yesterday...The utmost respect was shown the deceased. The business houses were all promptly closed and the citizens turned out en masse to attend the funeral." One man admitted that he wanted to see what the preacher could say about "the old cuss." The "penniless orphan boy" was laid to rest beside his monther, also an early citizen of Dahlonega. His brother, Jesse. who did not get bad publicity, is in the cemetery lot too. There are three imported Italian marble tombstones. Harrison's epitaph read, "Let his faults be buried with his bones." That was never done, but his Inn is a more serene subject.

The Rossignols wrote that it was a pleasure to sit at Riley's table, after staying so long at Choice's. They were happy that their rent was only $32.00 a month for the three of them and they could bring their own servants. At Choice's they paid $50.00, with an additional charge for domestics. They were also pleased with the hotel's large number of gentlemen transients.

Andrew Sparks, editor of the Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine described Riley's hotel. Having often seen the building while teaching at the college in Dahlonega, he wrote on September 15, 1960, "It was almost half a block long, had two elliptically arched doorways, six dormers with arched windows, and paneled rooms with beautiful mantels and heart-pine wainscots. According to legend, there was once an upstairs bridge across the street to a tavern and gambling establishment that Riley ran on the side. (A newspaper item verified the existence of this bridge. The editor wrote that the last of the building, now being torn down, once belonged to Riley and was connected to his hotel by a bridge constructed across the street. "Riley used to have a band, and the musicians would walk back and forth across the bridge and in the porches of the two buildings and play for the many guests and the citizens generally.") The Eagle was such a fine structure that the government's Historic Buildings Survey had it reprinted for the Library of Congress."

A short time before Riley died, he sold the Eagle to William Roberts, President of the Augusta and Dahlonega Mining Company. Next it was bought by Charles A. Besser and it became the Besser House. Besser, born in Germany, came to Dahlonega in 1841 and followed the tailor and mercantile business. In 1850, he joined those going to the gold fields of California. Upon his return, he began buying property in Dahlonega and became a prominent citizen. He was elected a member of the board of trustees of the North Georgia Agricultural College in the town and made speeches on important occasions.

In 1898, Besser became too feeble to live alone . He went to Atlanta to be with his two sons and soon died there. He had said that he wanted to spend one more night in his little home in Dahlonega so his sons carried him there the day before he was buried between his two wives in Mount Hope Cemetery. The editor of the Nugget, in writing the account of Besser's death, could not resist telling this funny story: The water used by the Besser House had to be brought from the public well on the Court House grounds Besser had sent his son for water and saw him loitering at the well. He went out and was giving the boy a thrashing when Mrs. Long came from the other side of the square telling Besser that he had no right to whip other people's children. Besser, embarrassed, answered, "well the boy has no right to look like my Bismark."

In June of 1898, the Besser House was being repaired by Frank W. Hall who had just bought it. Perhaps that was when the scars in the walls, made during Riley's gun battle from porch to street, were filled with putty and painted over. Hall took down the "Besser House" sign and put up "Hall's Villa". Frank W. Hall was more closely connected with "The Hall House" and his story will be told with the story of that hotel.

Hall bought the Eagle/Besser House/Hall's Villla late in his life and the operation of it was done mostly by others. After Hall's death, John H. Moore bought the hotel from Hall's estate and deeded it to the State of Georiga to be used as a dormitory for North Georgia College. It was during this time that is was called the Wigwam.

The grand old Eagle was a pile of ashes on January 9, 1942 when it burned to the ground.

The State deeded the lot back to Mr. Moore and at his death, it became the property of his son, Henry Moore. Henry erected a building to house his Ford dealership and a building beside it for a hardware store that was his son, Biilly's, business. This information concerning the Moore connection was furnished by Billy Moore, now 75 years old.

Today the buildings are divided into shops catering to the tourist trade.

The Porter Springs Hotel

|

| Porter Springs. Courtesy of Georgia Department of Archives and History |

According to legend, a mineral spring was first found there by the Cherokees. Its waters kept an Indian maiden young and beautiful, until she was carried away by a chief of the tribe. Without the water, she aged and asked to be carried home to the spring, where she died. Trahlyta's grave is the pile of rocks ten miles above Dahlonega in a triangle of roads known as Stone Pile Gap.

In 1868, the spring was discovered by Joseph H. McKee, a Methodist preacher, on land then belonging to Basil S. Porter. McKee and William Tate, a Baptist preacher, tested the water (in their fashion) for minerals and advertised their findings. People came from miles around pitching tents or taking home gallons of water, and claimed cures of rheumatism, dyspepsia, dropsy and many other diseases, even leprosy.

In a short time, the news of this miraculous water had spread far and wide and hotel accommodations were provided for people living at a distance, such as Hon. Alexander H. Stephens and Hon. Henry P. Farrow. Farrow leased and then bought the property, improved and enlarged the hotel, added entertainment, and the place became a recreational resort. When the hotel was overflowing with guests, the hacks that transported the clientele from Gainesville (the nearest railroad station) were notified not to bring more.

In the meantime, cottages and a chapel had been built on the lots across the street from the hotel. During the summers of 1913 and 1915, I lived in a cottage with my mother and siblings.

By the middle of the 1900s, the place was abandoned. Maybe the good of the water was counteracted by the rich cuisine, such as fried ham, hot biscuits and red eye gravy, or maybe it was just the fickleness of man, who is always looking elsewhere, as did the gold diggers of Lumpkin County.

Porter Springs can no longer be reached by a road. The rambling old hotel rotted down little by little; trees now cover the place and Trahlyta's spring again flows in solitude.

The Brierpatch Hotel

Brierpatch Hotel on the Calhoun Mine Property. Courtesy, Georgia Department of Archives and History |

Stillman wrote that George Montgomery, the next owner of the Calhoun property, dismantled the old Brairpatch Hotel.

The Tate Hotel

Tate Hotel. Courtesy, Georgia Department of Archives and History |

Around the year 1900, Tate Hotel, a commercial establishment, was built by James E. Tate on Dahlonega's Main Street. Mr. Tate was killed in an automobile accident in 1925. Before many years, the building was being used for county offices, among them the Welfare Department. In a few more years it gave way to progress.

The Mountain Inn

Lumpkin County's biggest ever hotel was on a hill two blocks north of Dahlonega's public square. Andrew W. Cain writes about it in his History of Lumpkin County and Anne Dismukes Amerson tells her story of it in the Winter 1994 issue of the North Georgia Journal .Professor Cain was more interested in the people who built the hotel and the events leading to it, than in the hotel. He quoted the Dahlonega Nugget of June 30, 1899, when it told of capitalists and mining men from Illinois, Ohio and North Carolina coming to Lumpkin County to examine the ore beds. They were satisfied with both the quality and quantity of the gold that they saw. Treating ore with a new method, a chlorination plant, they would save 95 % of the gold at a cost of 50 cents to $2.50 per ton, so they could work low grade ore at a good profit.

On March 30, 1900, the Nugget said, "The boom is certainly on in Dahlonega right now." The plant of the Dahlonega Consolidated Gold Mining Company was in operation and the owners constructed an elegant clubhouse for themselves.

|

| Stock certificate from the Dahlonega Consolidated Gold Mine. Courtesy Gold Rush Gallery |

On November 30, 1900, the Nugget quoted State Geologist Yeats as saying that the Consolidated had a capital stock of $5,000,000 and had purchased a dozen or more of the best known gold properties in Lumpkin County. In describing the plant in detail, he said that it had 120 stamps and a chlorination plant, with a capacity of forty tons of concentrates per day. The rock crusher weighed 18,000 pounds. It took four days to transport it the twenty-five miles from Gainesville on a wagon with steel tires, six inches wide. Sixteen mules were used to move the wagon, twelve pulling and four pushing.

Cain added, "Bright as were the prospects of this great company, it seemed doomed to failure. In 1906, the property was sold at a trustees' sale in the hope of satisfying a $175,000 financial obligation. The property was bid off for $20,000."

The Mountain Inn, later known as the Zimmer Mountain Lodge. Burned in May 1939. Courtesy Gold Rush Gallery |

Dr. Craig Arnold bought the private clubhouse and made it into a hotel for the public. He called it "The Mountain Inn" and in advertisements, he boasted of its "thirty acre" grounds, electricity and running water, the cuisine, the comfortable climate and an interesting clientele. In summer, people came from South Georgia and Florida to escape the heat. In winter, they came from Philadelphia and points north to escape the cold.

Anne picked up where Cain left off with the Consolidated's loss of their clubhouse. She described the landscaping of the Mountain Inn grounds, the spaciousness of the building and its distinguished guests. Pathways were laid out amid rare flowers, trees, shrubs and a lily pool. The forty-five room resort hotel's lobby had a massive stone fireplace with gold flecks in the rocks glittering in the firelight. The guest lists included Hollywood stars and directors who were making movies in the area.

In 1922, I worked on the same hill where the hotel stood, in a much smaller uninteresting wooden building that housed the Dahlonega High School. The thing that I remember first about the Inn was told me by "Mr. Bob" Meaders, a leading businessman of the town. Under the Clubhouse/Inn/Lodge was an old mining tunnel. The building's cesspool was a gold mine.

Sometime during the end of the 1920s, Arnold sold the Inn to W. V. Zimmer who had managed hotels in Detroit and Atlanta. The name of the hotel was changed to "The Mountain Lodge." Zimmer and son, Bill, had a successful but short time in the historic building. The father died and in settling his estate, it was learned that Arnold had sold acreage that he did not own. With the sale null and void, the building stood empty for several years. Bill Zimmer remained in Dahlonega working with the branch of government that was trying to save diseased trees in the Chattahoochee National Forest.

One night, the old hotel went up in flames. Anne Dismukes Amerson wrote, "Some accounts maintain The Mountain Lodge was struck by lightning, but there were also rumors that it was torched for the insurance money. The truth will probably never be known."

I vividly remember the night the huge wooden building two blocks north of the town square burned. I was sleeping in a much smaller, but still large wooden building one block south of the square, the home of "Aunt Nine" Head. The citizens of the town were awakened by a light as bright as the coming of day.

The Mountain Lodge burned in May of 1939.

The Hall House

Frank W. Hall came from Vermont to Dahlonega in the mid 1870's. He was a poor man then but not for long. In fact, according to the newspapers, he was the richest man in Lumpkin County before he died.

|

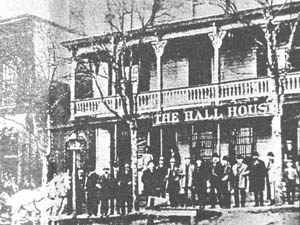

| The Hall House. Courtesy, Georgia Department of Archives and History. |

Editor Townsend published in the Nugget on March 23, 1923, "Many years ago Capt. Frank Hall harnessed the Hightower river up in Davis district, built a big saw mill and a grist mill, operated a large tannery and a store and a United States Post Office and called the place Jay A number of cottages were erected and were soon occupied. The leather was shipped to distant markets and a sale was found for large amounts of shingles and lumber hauled to market over very narrow, muddy, rough roads. He did a big business there for years and Jay was a thriving little town. But there is nothing there now to mark the once very busy place".

Among the buildings erected by Hall were Hall's Block on the northwest corner of the town square on lots 18 and 19, which was a commissary, and the building beside it, sometimes used as a hotel called "The Hall House." Isaac W. Waddell, president of North Georgia Agricultural College 1893-1897, leased the hotel for a home. When Hall's estate was settled, both buildings were bought by John H. Moore, who had worked as a laborer at 75 cents an hour when they were being built. The corner building was Moore's store for many years where everything was sold including coffins, clothing and collard greens. He divided the other building into apartments. Later the front rooms were were used for offices and shops. In the 1930's Bill Zimmer's office, when he was an employee of the U.S.Government, was there. Still later his wife, Evelyn, and I had a dress shop across the hall from him where the plate glass windows is that Mr. Moore installed for us in the late 1930s. Today, both buildings are divided into a maze of little shops serving a tourist town.

Over the years, many Boarding Houses and Rooming Houses: gave temporary homes to townsmen and to students of North Georgia College. Places, called Bed and Breakfast, furnished accomodations to Dahlonega's guests.

Frank W. Hall became an influential citizen of Lumpkin County. He was a trustee when Lumpkin first got public schools and was a member of the local board of trustees of North Georgia Agricultural College. He represented Lumpkin in the state Legislature and was Mayor of Dahlonega. When Hall bought lot 110 and started to build a home for himself, he struck a rich vein of gold while excavating for a foundation. Even though he was a rich and powerful citizen, the city fathers would not consider mining being done within a block of the town square. Hall could understand for he had valuable property on the square so he built his house on top all of this gold. He lived there until he moved to Ingleside, Georgia in the year 1900 and died there in October of 1901 of typhoid fever.

Of all the buildings erected by Hall, the most beautiful example of architecture was the jail house that he built for the county. It can be seen today at the foot of the hill which is the entrance to the present court house and other county buildings.

At Hall's death, years of liquidation of his large estate began.

The Smith House

Recent photo of the Smith House (visit their web site at www.smithhouse.com ). Photo courtesy Gold Rush Gallery. |

Henry Benjamin and Bessie Smith bought the house in 1922, which Hall had used as his residence, and thus began a hotel that was also a boarding house. I lived there in 1923 while teaching at the Dahlonega High School. I don't remember how much I paid for board but it couldn't have been very much, for my salary was $50.00 a month. To this day I do remember the mountain cabbage and a sweet potato casserole that Bessie Smith served. We sat at a long table and passed this and other good food to perfect strangers - the traveling public.

Ben Smith was a very civic minded citizen and sometimes ran for county office. His platforms were for improvement such as the stock law. The mountaineers didn't want change, so Smith was never elected. A witty old carpenter named Mr. Long was doing some work on the college campus and asked Martha Hutcherson, who came to the college as a librarian, "Are you going to vote for me in the coming election?" When she asked him what he was running for he said, "I don't know yet. I'm waiting for Ben to come out. He ain't never won any election yet and I am going to run against him."

Mrs. Smith died in 1939 and Ben ran the Smith House for a year or two but then sold it to William M. Smith, a New York lawyer. Will was not related to Ben, but he had once lived in Georgia. It was generally known that he had to leave Atlanta at the same time Governor John M. Slaton left and for the same reason - the Leo Frank case. All but the young will remember that little Mary Phagan was murdered in 1913 at a pencil factory in Atlanta and that superintendent Leo Frank, a Jew, and janitor Jim Conley, a negro, were suspects. Ward Greene was a reporter for the Atlanta Journal at the time and later told the story in his book, Star Reporters and 34 of Their Stories .

Greene wrote that Thomas E. Watson, the defeated Populist candidate for president, was at his home in Thompson, Georgia, licking his political wounds. His popularity was at a low ebb, so he latched onto the Leo Frank case, Jewish gold and yankee meddlers, to stir up his "woolhat" boys and get himself back in the news. Passions flared, the jury found Frank guilty and he was sentenced to die. The Governor, "entertaining a reasonable doubt," commuted the death sentence to life imprisonment.

A mob went to Milledgeville, took Frank from prison, carried him to Marietta, Georgia, Mary Phagan's home town, and hung him. A rabble marched on Slaton's home. In fear of losing his life, the Governor left the state.

Leonard Dinnerstein wrote in his book The Leo Frank Case , published in 1966, that Slaton was influenced in his decision to reduce the sentence by William M. Smith, Jim Conley's lawyer. Will had said, after his client was cleared of the murder, that he thought Conley was guilty. Will Smith had placed his life in danger also.

Attorney Smith bought Dahlonega's newspaper, the Nugget . The mountaineers didn't like his type of news, for he, too, advocated a stock law. His subscribers became so few that he sold all his holdings in Dahlonega and bought a farm a few miles to the north, near Stone Pile Gap, where the R Ranch, a time share vacation spot, is now located. Reportedly, he was soliciting money to build a school for mountain children when he died.

William D. Fry was the next owner of the Smith House. He turned the management of the dining room over to Fred and Thelma Welch. They were managers so long that their little son, Freddie, grew up there; Freddie talked his father into their buying the Smith House.

Now Freddie and his wife, Shirley, are the managers of the hotel that has fed many distinguished guests, including Bob Hope, Tip O'Neill and "Daddy" Barnes, North Georgia College's beloved math professor, who lived there. If you go to the Smith House today, you can sit at the long table with only the floor between you and a vein of gold and eat mountain cabbage and the sweet potato casserole that tastes very much like the one Bessie Smith served years ago, then pass it on to perfect strangers.

The old miners, who paid for their drinks at Nuckolls' Tavern with the gold dust that would stay on the point of a knife, would never believe that the Smith House was accepting a piece of plastic in payment for their services.

With the Smith House, which is still in operation as a hotel, all of the known Inns in the gold fields of Lumpkin County are accounted for.

Sprawl's Hotel

Wait! There should be no list of Inns without mentioning "Sprawl's Hotel." Let Col. W. P. Price, a life long and most respected citizen of Dahlonega, tell about it as he told it over a hundred years ago: In the early days of Dahlonega, "Gambling houses, dancing houses, drinking saloons, houses of ill fame, billiard saloons and tenpin alleys were open day and night. Water Street where there is now no street and not a house standing, but where many stood fifty and sixty years ago, was the street where hundreds of miners and other people gathered, especially on Saturdays and Sundays, and made 'night hideous' by fighting, cursing and swearing. Women were almost as numerous as men, and equally as vile and wicked.""In 1845 the writer was a printer boy and newspaper carrier. He made the round of Water Street as quickly as possible. At the lower end of the street was a tanyard, of which there is some evidence yet to be seen. The vats were unenclosed by any fence, and this spot enjoyed the euphonious if not appropriate name of 'Sprawl's Hotel.' Many drunken fellows were carried by other fellows, not so drunk, to the place, being told that the hour for retiring had arrived, and the poor fellow, marching between 'two friends' would be unceremoniously walked off into the tan vats where they were allowed to 'ooze' themselves: as Shakespeare hath it: 'My son in the ooze is bedded.'"